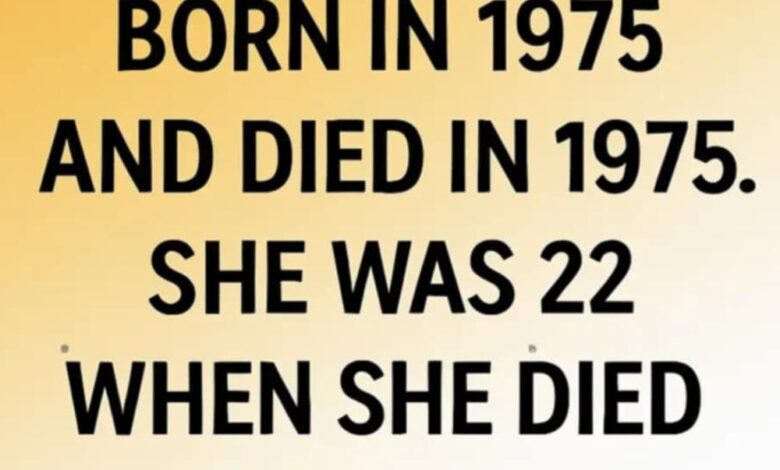

In the vast, interconnected landscape of the modern internet, few things possess the viral potential of a perfectly constructed paradox. The digital age has fostered a unique fascination with lateral thinking puzzles—riddles that appear to defy the laws of logic until a single, hidden detail is unearthed. Recently, a specific linguistic puzzle has swept across social media platforms, migrating from niche message boards to the mainstream feeds of millions, sparking a global debate that highlights the fascinating ways the human brain processes information. The riddle is deceptively simple, consisting of only a few short sentences: “A woman was born in 1975 and died in 1975. She was 22 years old when she died. How is this possible?”

At first glance, the statement reads like a clerical error or a mathematical impossibility. Our cognitive architecture is conditioned to look for patterns, and in the context of four-digit numbers beginning with “19,” the brain almost instantaneously categorizes the information as a chronological date. This is the primary mechanism of the riddle’s success: it exploits a psychological phenomenon known as mental set, where individuals approach a problem with a pre-established framework. Because the year 1975 is a well-known historical marker, the reader immediately assumes they are looking at a timeline. Within that framework, the math simply does not hold up. If a person is born and dies in the same calendar year, their lifespan is measured in months, days, or hours—not decades.

The viral explosion of this puzzle began on February 4, 2026, as users on platforms like X, TikTok, and Instagram began sharing the prompt, often accompanied by frustrated captions and lengthy comment threads filled with wild theories. Some users speculated that the woman might have been born in a leap year, or perhaps she was traveling near the speed of light, invoking Einstein’s theory of relativity to explain time dilation. Others suggested more macabre or supernatural explanations, ranging from reincarnation to the idea that the woman lived in a region where the local calendar system differed vastly from the Gregorian standard. The beauty of the puzzle lies in this frantic search for complex answers to what is, in reality, a very simple linguistic trick.

As the discussion intensified, the “solution” began to circulate, providing that satisfying “aha!” moment that characterizes the best brain teasers. The resolution of the paradox hinges on the recontextualization of the number 1975. The riddle does not state that she was born and died in the year 1975; it simply provides the number as a location. The woman was born in hospital room 1975, and twenty-two years later, in a poetic but tragic coincidence of fate, she passed away in that very same room. Once the reader shifts their perspective from a temporal measurement to a spatial one, the logical contradiction vanishes entirely. The numbers remain the same, but their meaning is transformed by a single change in the assumed preposition.

This specific riddle serves as a profound example of how human perception is governed by context. In the field of linguistics and semiotics, this is often referred to as “priming.” By presenting a number that fits perfectly into the expected format of a year, the author of the riddle primes the audience to think about time. We are so accustomed to seeing four-digit numbers used as dates that we stop seeing them as mere integers. This cognitive shortcut is usually efficient, allowing us to navigate the world quickly without over-analyzing every piece of data. However, as this viral trend proves, those same shortcuts can be used to lead us into a logical cul-de-sac.

The “Room 1975” riddle also touches on the nature of digital engagement in the mid-2020s. In an era of short-form content and rapid-fire scrolling, a puzzle that can be consumed in five seconds but takes five minutes to solve is the ultimate currency for engagement. It encourages users to stop, think, and—most importantly for the algorithms—comment. The comment sections of these posts became a microcosm of human behavior, showcasing everything from the “know-it-all” who posts the answer immediately to the “skeptic” who argues that the riddle is poorly constructed because hospitals rarely have room numbers that high. The latter point actually fueled even more discussion, as users began researching hospital floor plans and numbering conventions, proving that even the flaws in a riddle can contribute to its longevity.

Beyond the entertainment value, educators and psychologists have pointed to this viral sensation as a valuable tool for teaching critical thinking. It demonstrates the importance of challenging one’s own assumptions and looking for alternative interpretations of “factual” statements. In a world where misinformation can often be spread through the clever manipulation of context, the ability to step back and ask, “What else could this number represent?” is a vital skill. The riddle acts as a low-stakes training ground for the brain, reminding us that reality is often dictated by the lens through which we choose to view it.

The emotional resonance of the story, even as a fictional construct, also played a role in its spread. The idea of a life coming full circle—beginning and ending in the exact same physical space—carries a certain narrative weight. It evokes a sense of symmetry and irony that captures the imagination. While the woman in the riddle is a hypothetical figure, the scenario creates a vivid mental image that sticks with the reader longer than a purely abstract mathematical problem would. This “narrative hook” is what separates a dry logic puzzle from a viral story.

As the trend eventually begins to fade, replaced by the next internet mystery or meme, the “1975” puzzle will remain a classic example of lateral thinking. It joins the ranks of other famous riddles, such as the one about the man who lived on the twentieth floor and only took the elevator to the tenth floor on sunny days (because he was a person of short stature and could only reach the higher buttons with his umbrella). These stories persist because they remind us of the fallibility of our own logic. They celebrate the quirkiness of language and the infinite ways in which words can be arranged to hide the truth in plain sight.

In the end, the viral mystery of the woman who lived twenty-two years between two “1975s” is less about the woman herself and more about the people trying to solve her story. It is a testament to the human desire to make sense of the nonsensical and to find order in chaos. Whether viewed on a smartphone screen in a crowded subway or discussed over a dinner table, the riddle serves as a brief, shared moment of intellectual play—a small reminder that sometimes, the answer we are looking for is right in front of us, hidden only by the narrowness of our own expectations. When we finally realize that 1975 was a room and not a year, we don’t just solve a puzzle; we experience a momentary expansion of our own cognitive boundaries, a small but significant shift in how we choose to interpret the world around us.